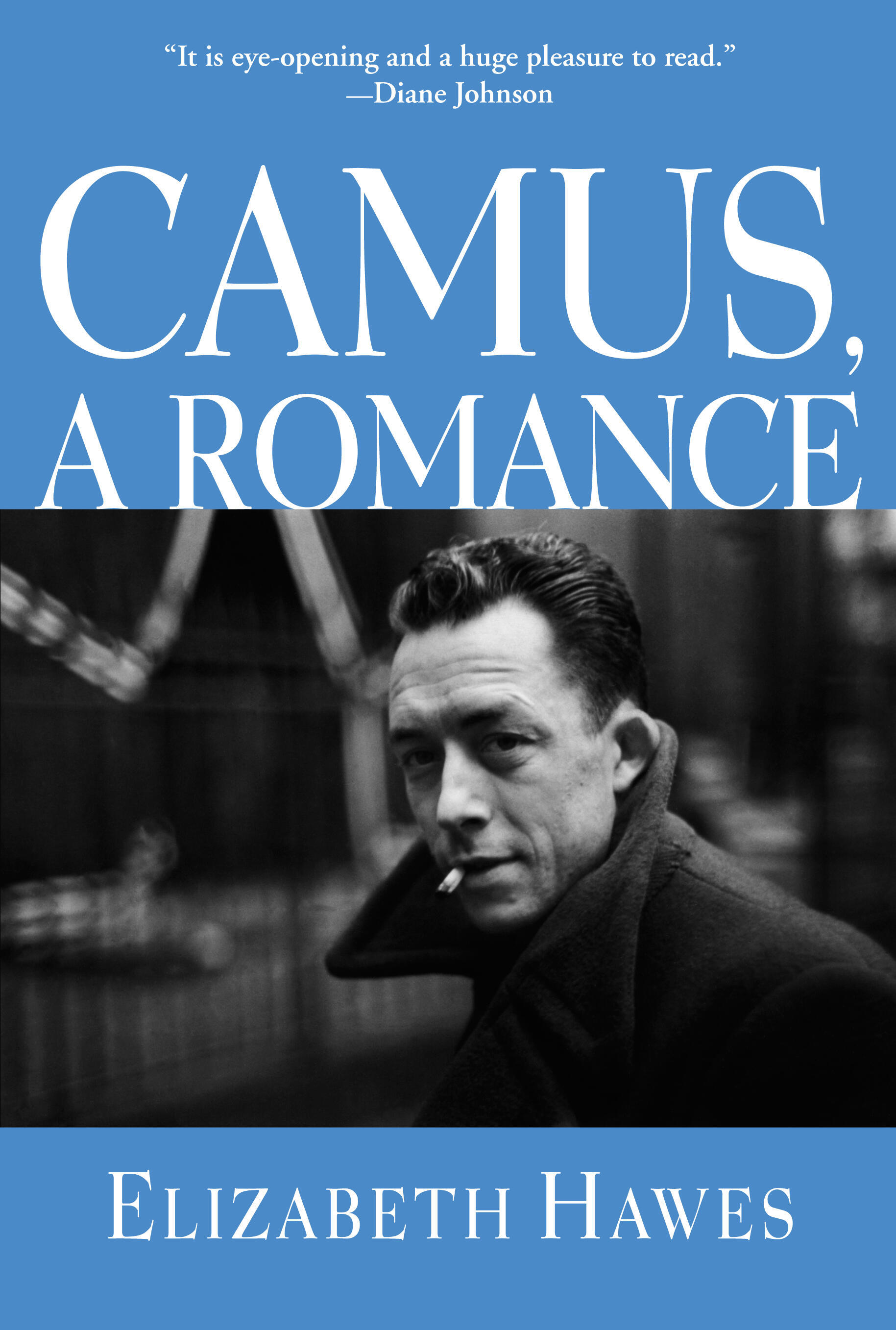

American teenager Elizabeth Hawes fell in love with Albert Camus in the late 1950s. Camus's novels inspired her with a "feeling of connection, compassion, and love for all of mankind" and she experienced the “bonding of two souls”. But any hope of meeting her idol ended in 1960 with his sudden, violent death at 46. Now she has written his biography.

Intellectuals on both sides of the Atlantic grieved over the photograph of the sports car Camus died in, wrapped around a tree, with his briefcase hurled into the mud.

"Rarely,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre, “has the historical moment so clearly demanded that a writer go on living."

Today the reputation of the French-Algerian author, who won the Nobel Prize in 1957, is largely based on three novels - L'Etranger (The Stranger, 1942), La Peste (The Plague, 1947) and La Chute (The Fall, 1956).

He explored free will and the seemingly futile search for meaning in essays like The Myth of Sisyphus, but Camus the thinker was snubbed by Sartre and his followers after the publication of The Rebel, an essay on revolution that denounced all forms of authoritarianism.

Fifty years after his death, Hawes probes both his life and her lifelong passion in a book that is part biography, part personal memoir:

"Sometimes I feel almost like his wife or his sister as well as his reader, student, and Boswell, watching over him, worrying about his health or his spirits," she writes. She chronicles Camus, the man of action ready to sacrifice his life for France, but also the recluse, noting "two elements in constant opposition, the solidaire and the solitaire".

The recluse was a man living under a death sentence in the form of tuberculosis.

“It is a particular form of exile within the general sense of exile that ruled his life,” explains Hawes. “He was struck very young with TB as an adolescent at 17. The most severe bouts were after the war. He was exhausted by his work for the underground [resistance] newspaper, Combat.

"The fact that people don’t talk about his TB is a reflection of his success in keeping it private. His sudden and tragic death eclipsed the fact that he probably would have died of it.”

Hawes writes appreciatively of the remarkable women in Camus’s life though the countless love affairs pushed his last wife, Francine, into depression and attempted suicide.

“In the end, I felt I had to stop short of pop-psych about why he had so many women. There were probably a lot of reasons including his mother and his failed first marriage that disillusioned him but he was a very physical, sensual person. In the last couple of days of his life before his car accident he wrote letters to four women, passionately anticipating a reunion.”

The publication of Camus’s unfinished novel in 1995, The First Man, rekindled Hawes’s obsession and moved her to write a book about him.

First Man is the story of a European in Algeria, "the story of an alien," writes Camus in his notes.

In his last days, the Algerian revolution called into question Camus’s politics and identity. He “still believed in the future of a multicultural Algeria, even as Arab bombs exploded under his mother's window,” writes Hawes, “that was his dilemma in the last days of his life.”

Daily newsletterReceive essential international news every morning

Subscribe